How do vaccines work? What is herd immunity?

Hey there, health enthusiasts and curious minds!

Join me on a whirlwind tour of the incredible world of vaccinations. It’s a topic that’s as fascinating as it is vital for our well-being. Picture your immune system as a dedicated team of superheroes. They’re always ready to fend off the villains, which are those pesky germs and viruses. In this analogy, vaccines are like the ultimate training camp. They prepare our heroes, with the know-how they need to keep us all safe and sound. Keep reading to learn about the remarkable history behind this training camp. Discover how YOU can be a hero and protect people in your community!

The History of Vaccinations

Let’s travel through time and explore the milestones transforming how we protect ourselves and our communities.

Ancient Times: Early Variolation in China, India, and Africa

Long before the advent of modern medicine, various ancient civilizations discovered the principle that exposure to a mild form of smallpox could confer immunity against more severe forms. This practice, known variably as variolation or inoculation, involved deliberately introducing small amounts of smallpox material into the skin. Notably, in China, variolation practices were documented as early as the mid-16th century. These practices were possibly based on earlier traditions. The traditions were attributed to Taoist or Buddhist monks around 1000 AD. By the 17th century, variolation was widespread among the Chinese royalty and military. The process often involved insufflation or blowing dried smallpox scabs up the nose of the person being inoculated.

In India, similar practices were observed. Techniques involved a sharp iron needle to introduce smallpox material into the skin. Itinerant Brahmins notably practiced these techniques. They were described in 18th-century accounts. Despite modern claims, there is no evidence in ancient Sanskrit texts for such practices. Instead, the practice appears to have been established several centuries prior to its documentation in the 16th century.

In Africa, the practice was widely used among various communities and was known to the Arabs in North Africa well before 1700. Historical accounts describe the process as involving an incision on the hand. Matter from smallpox pustules was inserted into this incision. The treated individuals developed only mild forms of the disease.

The practice also found a foothold in parts of the Ottoman Empire by the 17th century, introduced by communities such as the Greeks and widely adopted during severe smallpox epidemics. In 1716, Jacob Pylarinius, a physician in Turkey, reported that inoculation had been introduced into Constantinople around 1660 by a Greek woman.

“This method involved carrying children to an individual suffering from smallpox when the pustules were fully mature. A surgeon would then make an incision between the thumb and fore-finger of the child’s hand, inserting matter from the pustules. The wound was covered to protect it from air exposure, and within a few days, a mild form of the disease would manifest, typically conferring immunity without severe illness.”

Pylarinius confirmed this practice with personal testimony. He noted its efficacy and safety. He highlighted that it was so ancient in the regions of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algier that its origins were untraceable. It was commonly practiced among both town dwellers and nomadic groups.

1717: Lady Mary Montagu in Turkey

In 1717, Lady Mary Montagu, a smallpox survivor, traveled to Turkey and encountered a fascinating practice. She observed elder women performing a unique form of inoculation.

“The old woman comes with a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks which vein you please to have opened.”

Impressed by the method, she had the procedure performed on her 8-year-old son and later brought this innovative technique back to England, paving the way for broader acceptance of inoculation.

1721: Smallpox Inoculation in Colonial America

Across the Atlantic, a remarkable story unfolded in colonial America. Onesimus, a slave from the Guramantese people of southern Libya, shared with his master, Reverend Cotton Mather, the method of vaccination practiced among his people around 1706. This involved making a small cut and inserting material from a smallpox sore to induce a mild case and confer immunity. Mather, intrigued and convinced by Onesimus’ scar and explanation, became a proponent of inoculation. In his correspondence responding to Dr. Emanuel Timonius’ report on inoculation, Mather mentioned that he had learned about the practice from Onesimus well before it was widely known in Europe, describing Onesimus as “a pretty intelligent fellow” who had explained that the inoculation was a common practice among the Guramantese and assured protection against smallpox.

1796: Edward Jenner’s Cowpox Breakthrough

The late 18th century brought a revolutionary leap in immunization. In 1796, English physician Dr. Edward Jenner observed that milkmaids who contracted cowpox—a much milder illness—appeared immune to smallpox. By using scrapings from cowpox lesions to inoculate his patients, Jenner demonstrated that a controlled exposure to a related, less dangerous virus could confer immunity against a deadly disease. This discovery laid the cornerstone for modern vaccination and introduced the term “vaccine” (from “vacca,” meaning cow).

1885: Louis Pasteur and the Rabies Vaccine

Building on Jenner’s work, French scientist Louis Pasteur made further strides in the field of immunization. In 1885, Pasteur developed the rabies vaccine, a breakthrough that not only saved countless lives but also proved that weakened or altered pathogens could safely train our immune systems. Pasteur’s innovations spurred further research and solidified vaccination as a critical tool in public health.

1955–1960s: Polio Vaccines Revolutionize Public Health

The mid-20th century saw dramatic progress with the development of vaccines against poliomyelitis—a disease that had paralyzed thousands. In 1955, Jonas Salk introduced the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), and later, in the 1960s, Albert Sabin developed the oral polio vaccine (OPV). These breakthroughs were monumental in reducing polio’s impact worldwide and showcased the power of vaccines to eradicate debilitating diseases.

Early 1960s–1970s: The Dawn of mRNA Research

In the early 1960s, scientists discovered messenger RNA (mRNA), a molecule that carries genetic instructions from DNA to cells. By the 1970s, researchers were exploring ways to deliver mRNA into cells, but they encountered a significant hurdle: mRNA was rapidly degraded by the body before it could do its work. This challenge sparked a wave of innovation, setting the stage for the next breakthrough.

2014–2020: Nanotechnology and mRNA Vaccines Take Shape

The solution came with the advent of nanotechnology. Scientists developed lipid nanoparticles—tiny, fatty droplets that wrap the mRNA like a protective bubble. These lipid envelopes ensure that mRNA survives its journey into cells, where it can be translated into proteins. Early mRNA vaccine candidates were even developed against the Ebola virus, with clinical trials taking place during the 2014–2015 West African outbreak, compassionate use in Guinea in 2015, and further testing during the 2018–2020 eastern DRC outbreak.

2020–2021: mRNA Vaccines and the COVID-19 Pandemic

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the world witnessed an unprecedented surge in vaccine development. While some candidates used traditional adenovirus vectors—like the Johnson & Johnson vaccine—the decades of mRNA research were primed for their moment. mRNA vaccines instruct cells to produce the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, priming the immune system to recognize and combat the virus. This technology proved to be extremely safe and effective, culminating in Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine becoming the first mRNA product to receive full FDA approval in the U.S.

From ancient variolation to the cutting-edge mRNA breakthroughs of today, each chapter in this history reveals a story of human resilience and ingenuity. Every step, from Lady Montagu’s Turkish adventure to the high-tech labs of the COVID-19 era, reminds us that while our methods evolve, the core principle remains unchanged: safely priming our immune system to protect ourselves and our communities.

How does vaccination keep our communities safe?

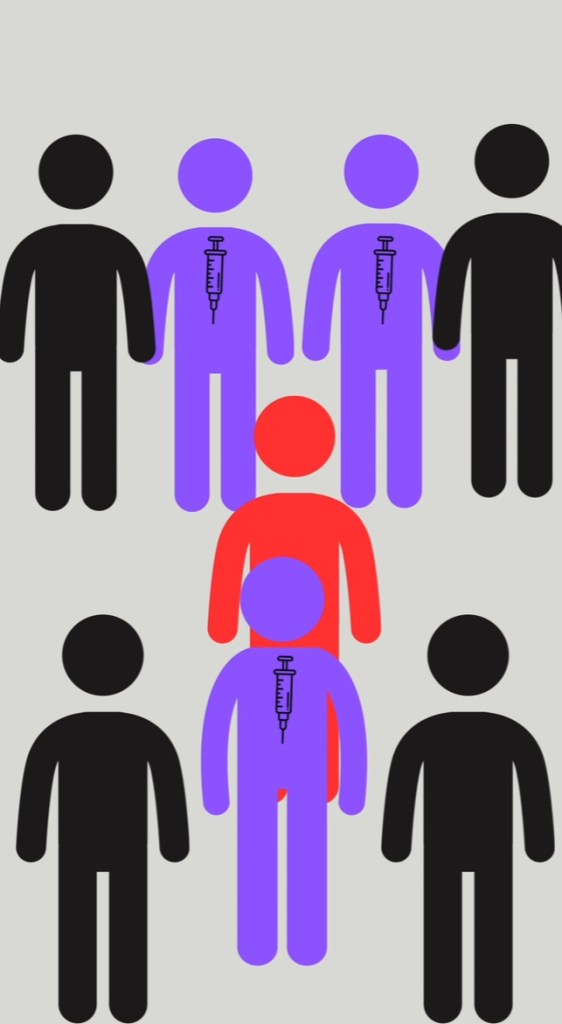

Vaccination primarily serves at the individual level, offering protection to ourselves and our families. However, when a significant portion of the community receives vaccinations, it contributes to a broader protective measure known as herd immunity. This occurs when enough people in a community are immunized against a disease, thereby limiting its spread and protecting those who are most vulnerable.

Vulnerable groups include infants who are too young to be vaccinated and are highly susceptible to infections. Elderly individuals also may not be able to receive certain vaccines due to health constraints, and others may have allergies to vaccine components, such as eggs, which are commonly used in the production of influenza vaccines. For these reasons, they depend on the immunity of the herd to prevent the transmission of diseases to them.

Herd immunity works by significantly reducing the number of potential hosts for a pathogen, thus impeding its ability to replicate and spread. Even if a pathogen enters a community, it encounters a large number of people who have immunological memory, which decreases the likelihood of its survival and transmission. Consequently, those who do become infected are less likely to develop severe illness or transmit the disease to others.

The principle behind vaccination extends beyond personal health; it is a crucial step in safeguarding the entire community. Each individual who gets vaccinated not only protects themselves but also contributes to the collective health security of the community, making it increasingly difficult for pathogens to trigger outbreaks. Therefore, by choosing to vaccinate, you are participating in a collective effort to protect and uphold the health of your community.

Unleashing Our Inner Heroes in the Fight for Public Health

From the early days of variolation and the do-good actions of Lady Montagu and Onesimus to Jenner’s groundbreaking cowpox experiments and the modern marvel of mRNA vaccines, the history of vaccination is a testament to human ingenuity and the power of collective action. Each innovation builds on the last, reinforcing that while our methods may evolve, the core principle remains: a safe, controlled exposure to a pathogen trains our immune system to protect us, creating a ripple effect of health and hope.

Just as superheroes undergo training to hone their abilities and protect those around them, each vaccination is akin to a session of superhero training, fortifying the individual and the entire community. So, next time you roll up your sleeve for a vaccine, remember—you’re not just protecting yourself; you’re engaging in an act of heroism, strengthening a community-wide shield that keeps us all safe, allowing us to move forward with confidence and care. By getting vaccinated, you become part of a lineage of heroes, each playing a pivotal role in the ongoing story of public health and communal well-being.

Beyrer, C. (2021, October 6). The Long History of mRNA Vaccines. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2021/the-long-history-of-mrna-vaccines

Boylston, A. (2012). The origins of inoculation. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 105(7), 309–313. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2012.12k044

Kallay, R. (2024). Use of ebola vaccines worldwide, 2021–2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2024(73), 360–364. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7316a1

Leave a comment